As an Environmental Scientist (not to mention the partner of a climate scientist!), I’ve wanted to write a post on the subject of carbon offsets for a very long time, even though it’s not technically in the purview of my current position as the quantitative ecologist for a research center studying invasive species. After seeing three of my favorite sources of robust popular science information–Vox, Wendover Productions, and Last Week Tonight–all cover the subject in recent times, though, I felt like I couldn’t wait any longer! I had to add my two cents to the discussion.

Like so many others, I am here to cast some shade on the idea. While a promising–and absolutely viable–approach to addressing the current climate crisis in theory, carbon offsets are a steep hill to climb in practice. They absolutely CAN work, but they are absolutely NOT the “quick and easy fix” they are sometimes purported to be. To be successful, they require serious due diligence on both the buyer’s and seller’s parts.

So, I’m going to frame this article as a checklist of sorts–if you are looking to offset your carbon emissions via offsets, you’re going to want to make sure your plan checks every single one of the “boxes” in this article. Spoiler alert: It’s quite a few boxes!

Before we get to the list, though, let’s quickly review what a carbon offset is and why you (or a company you shop at or work for) might buy one.

Carbon offsets (and the climate problem) in 90 seconds

Here’s the very brief version–if you want to know more, I’d suggest you consult one of the sources I link to above!

First, climate change (as we are currently experiencing it, anyhow) is a human-driven process wherein the climate (the long-term patterns of temperature, precipitation, and wind) is shifting at a global scale, although not always in the same ways in every place. Climate change is ultimately a product of global warming, another human-driven process. In global warming, heat energy (the ultimate product of solar energy coming from the sun) fails to escape Earth’s atmosphere out into space quite as quickly as it used to. As a result, our atmosphere retains more heat than it used to, and its average temperature increases.

Since heat is the “fuel” for the “engine” that is global climate, altering the amount of fuel in the system (in this case, by increasing it) results in a change in the behavior of the engine. Global warming is not the only way to cause climate change (global cooling would also do it, for example!), but it is the way we’re doing it now.

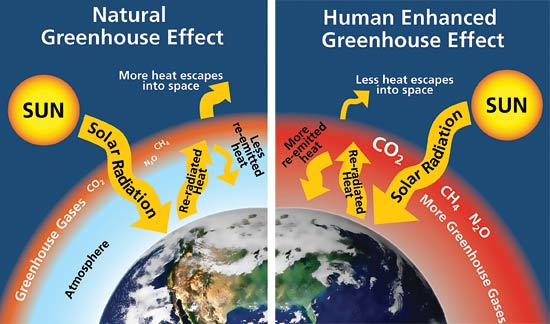

This begs an important question: Why, then, is the Earth failing to lose heat to space quite as quickly as it used to? The answer: An enhanced greenhouse effect, a third human-induced process. Greenhouse gasses are a very select group of gasses that, when they are floating in the atmosphere and encounter heat, absorb and re-emit that heat in all directions, including back towards the surface of the Earth. So, if you are a unit of heat, and you are trying to escape the Earth’s atmosphere, the more greenhouse gas molecules you encounter on your journey, the more often you are going to get delayed by their antics (i.e., sucking you up and spitting you all over the place).

So, to recap so far: Humans are enhancing the greenhouse effect, which is leading to global warming, which is leading to climate change. No, those three processes aren’t the same thing–they are three separate processes in a causal chain!

Now, I said earlier that greenhouse gasses are a select group. Most of the atmosphere is Nitrogen gas (N2), oxygen gas (O2), and noble gasses like argon (Ar). Even though those gasses make up 99%+ of the gas molecules atmosphere, none of them participate in the greenhouse effect–heat just passes right through them! Instead, it’s just a fraction of 1% of all gasses that do this; this goes to show that a little of these greenhouse gasses goes a long way!

Among these select few greenhouse gasses, the most notable are carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), nitrous oxide (N2O), and the chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), which are chemicals used in air conditioning among other uses [we’re going to ignore water vapor here because it just complicates things].

Methane is largely produced by things rotting underwater (e.g., soil in rice paddies), by leaks of natural gas fuel, certain kinds of digestion (e.g., that which occurs in cow stomachs), and decomposition that occurs in tight, airless spaces (e.g., such as in landfills). Nitrous oxide is often made wherever oxygen and nitrogen are in large quantities in the presence of microbes (such as in fertilized farm fields). Carbon dioxide is formed anywhere there’s decomposition (e.g., during deforestation) or combustion (e.g., in the engines of gas-powered cars).

While not quite every greenhouse gas includes carbon (e.g., N2O doesn’t), and while not quite every carbon-containing gas is a greenhouse gas (carbon monoxide, CO, has a negligible impact, e.g.), there’s a pattern here: most significant greenhouse gasses are carbon-based gasses. This is why we often talk about greenhouse gas emissions as being carbon emissions, even though such shorthand is technically incorrect. That’s why this article is about carbon offsets and not greenhouse gas offsets; we’d be talking about the same thing either way.

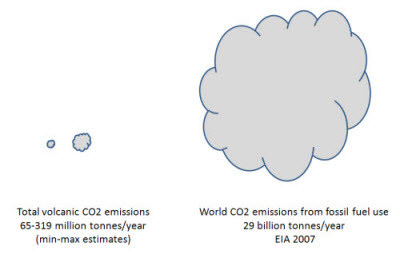

Hopefully, you can also detect another pattern in all the processes I’ve mentioned above–they’re all human-driven. Human activities release a huge amount of greenhouse gasses. That’s how we got into this whole mess!

If the problem, then, is that we are emitting too many greenhouse gasses into the atmosphere, and then these things are delaying too much heat from escaping the atmosphere, the solution seems obvious: take these GHGs back out of the atmosphere and stop putting so much there in the first place. That’s exactly the idea. Of course, natural processes can and do take greenhouse gasses out of the atmosphere (e.g., photosynthesis by plants). Under normal circumstances, we’d be able to rely on these processes to take care of things eventually. But current circumstances aren’t normal; we’re emitting far more of these gasses than natural processes can handle–we need to help the situation, and we need to do it quickly to reverse the damage we’ve already done.

This is where carbon offsets begin to come in! What if we gave nature a boost? For example, what if we plant a bunch more trees that can then do photosynthesis, pulling CO2 out of the atmosphere? Or improve the quality of our soils so they hold onto more carbon and nitrogen? Or fertilize the oceans, so flora there take up more carbon? All of these things would, at least in theory, take some carbon out of the atmosphere that we’ve put there.

There’s have also been attempts to develop so-called “carbon-capture technologies,” although these are still more fiction than science as I write this. Very basically, these would involve machines that could remove greenhouse gasses from the atmosphere and then convert them to forms that can’t escape again or that could be stored safely somewhere, such as underground.

A third avenue: Emitting fewer greenhouse gasses in the first place. Here, we could switch to using less greenhouse-gas-emitting fuels in cars or furnaces or stoves. We could also switch our planes and busses and cars out for versions that use different fuels or the same fuels more efficiently. Or we could change how we produce electricity by switching from things like coal power plants (burning coal emits a lot of greenhouse gasses) to solar panels (which emit virtually none once they’re manufactured).

We could also prevent decomposition or decay by, for example, preventing a forest from getting cut down somewhere. And some companies that otherwise might emit compounds such as chlorofluorocarbons as part of their operations might work harder to prevent those emissions if paid to do so.

The only problem with all these approaches (and these are really just the tip of the iceberg!) is that, well, they tend to be relatively expensive, at least compared to the alternative of doing nothing. Solar panels don’t install themselves, for example! And if someone was inclined to cut down a forest for economic reasons, the logic goes that you’ll need to make it worth their while to not do that.

Another problem with many of these approaches is that they may not make sense for you personally. Your activities may be generating greenhouse gas emissions, but your own options to reduce those emissions may not be all that great. For example, what if you have to drive 45 minutes each way for work, and you can’t afford a more fuel-efficient car? Or what if your roof doesn’t get a lot of sunlight, or you don’t own the home you live in? You may not be able to replace your furnace or install solar panels in your circumstances.

So, to recap: We understand what is causing the problem super well, and we have many well-understood options to help start to solve that problem, but there are two major hang-ups: Not everyone can afford the solutions, and many of the best solutions may not work in every situation.

As the old saying goes: With every problem comes an opportunity. Imagine that I emit a lot of greenhouse gasses, and I could afford solar panels, but my house doesn’t get a lot of sunlight. Meanwhile, imagine your house gets plenty of sunlight for solar panels, but so what? You don’t emit a lot of greenhouse gasses compared to me, so solar panels wouldn’t be as worthwhile for you. Besides, maybe you can’t afford them anyway.

There’s a deal to be struck here, right?! I could pay you to get solar panels. By doing so, emissions are reduced somewhere thanks to my money, and since you ultimately made that happen, you got paid for the trouble. I have just offset my carbon emissions. I didn’t reduce them –I may still be emitting just as much carbon as before–but I used money to help someone else reduce emissions on my behalf, which helps to balance out (or offset) the emissions I’m still making.

Bam! That’s a carbon offset program in a nutshell, even if most of the ones you’ve maybe heard of operate on a much larger scale. For example, an airline company might pay another company many millions of dollars to plant millions trees on their behalf. The airline keeps right on burning jet fuel, but, in theory, the trees they are paying for are taking a lot of those greenhouse gasses back out of the atmosphere. A win-win, right?

Not so fast. Now that we’re all on the same page in terms of what a carbon offset is and why someone would buy or sell one, let’s start building our checklist. As you go, I think you will start to see why there’s some collective skepticism about carbon offsets and their ability to achieve the win-win conditions they look like they should produce on paper.

Checkbox #1: Did you actually buy an offset?

Our first checklist item is also the most positively stupid one. It pains me that I felt I needed to add it to the list, but here we are. Here goes: For an offset to have occurred, an offset must have been bought.

What I mean is this: In our example above about the airline company, did the company actually purchase offsets? Or did they just say they did? After all, the financial records of private companies are often kept private; it may not be possible to prove that any money was actually spent or that any offset was actually purchased. To be clear, I’m not saying that this has happened yet in any identified instances that I personally know of, but you never know.

On a more personal level, might I recommend not claiming that you purchased a carbon offset if you really didn’t? Thanks in advance, signed all of us.

Checkbox #2: Did the person/company you bought the offset from actually do anything with your money?

Just as in any economic transaction, in a carbon offset, the idea is that both parties uphold their ends of the bargain. The purchaser provides the funds they said they would, and the seller actually provides the goods and/or services purchased. Herein lies one of the very real hazards of carbon offsets–it can be difficult to prove the seller has actually delivered on their promises.

Think about it: If you purchased a stove, and a stove never showed up at your house, you could be pretty darn sure you didn’t receive the stove you’d bought. Similarly, if you paid your neighbor to put solar panels on their house on your behalf, you could be pretty darn sure they’ve fulfilled their promise when you see solar panels pop up on their roof.

Carbon offsets are not always so easily verified, in part because they are very much unlike most other conventional goods. First off, unlike in the example I provided earlier, in a true offset program, you are often not paying your neighbor; you are paying a company. Imagine calling up Google or Meta or Comcast to verify they installed a solar panel somewhere on your personal behalf. Imagine asking them to prove which one it was. You *might* eventually get a “yes,” but it might be quite a hassle! And I doubt they’ll be putting a name plaque on your specific solar panel out in Utah or wherever for you.

Second, you are not always paying a company that operates anywhere near you or, for that matter, for an offset anywhere near you. Imagine it wasn’t your neighbor you paid to install solar panels; it was someone in Bangladesh. Often, carbon offset programs function as connections between wealthy, high-emitting people in wealthier countries (who may have means and motive but not the opportunity, so to speak) and poorer, low-emitting people in poorer countries (who may have opportunity and motive, but not the means). So, it’s not that strange at all for the “seller,” or at least the person who ultimately receives your solar panels or whatever, to be someone half a world away from you! Unless you’re going to fly to Bangladesh to see these solar panels for yourself, you’re kinda going to have to take someone’s word for it that they exist.

Third, what one is actually purchasing isn’t always as tangible as “one solar panel.” I’ll give you two examples. Imagine you purchased an offset, and someone was supposed to plant one tree for you. Trees tend to look alike (I’m a botanist–I’m allowed to say that). If someone shows you a picture of a tree, how easy would it be for you to confirm that it’s the tree you bought and not just some random picture of some random tree? How would you know the tree is alive, and in Norway, and it’s that tree and not that other tree that you helped get planted or saved?

Sometimes, you’re not even buying something discrete like “a tree.” Maybe you only spent enough money when buying your offset to buy 60% of a tree. Good luck getting them to show you exactly which 60% of exactly which tree you bought!

Plus, if you bought a tree with your carbon offset, guess what: trees take time to plant AND grow. It might take five years for that tree to end up in the ground somewhere! Until then, it’d be tricky for even a reputable offset purveyor to show you much of anything by way of a proof of purchase.

And this isn’t even to mention those offsets that involve taking greenhouse gases out of the atmosphere that are already there. I dunno if you’ve noticed, but gasses tend to be…well…invisible. Suppose you bought an offset, and someone was supposed to extract 1 ton of CO2 out of the atmosphere for you. What could they show you that would satisfactorily prove to you that they’d done so? A CO2 tank (which could be empty)? Do they have to bring the tank to you and blow all its contents in your skeptical face before you’d be satisfied? That might defeat the purpose…

Ok, ok, I think I’ve made my point: Verifying that the seller of a carbon offset has fulfilled their promise and actually done anything with your money can be more complicated than it seems! So, if you’re buying a carbon offset, you might want to give this some serious thought. How will you ensure the seller of your offset has done anything with your money other than pocket it?

Checkbox #3: Did the offset actually reduce emissions or remove GHGs from the atmosphere?

To me, this is the next logical question after the last one. Ok, so someone actually preserved a tree somewhere, or built a solar panel somewhere, or turned on their CO2-sucking machine somewhere on your behalf. Great! They’ve made what I will call an attempt to do what they’ve promised.

But that could be all it ends up being: an attempt. Sometimes, stoves are broken upon delivery. Trees sometimes die of pest outbreaks or get trampled by elephants. Solar panels sometimes get hit by hailstones and need to get thrown out. And, sometimes, idiot humans turn on CO2-sucking machines in reverse and no one notices for a few minutes.

My larger point here is this: once the economic accounting of the transaction is done, the greenhouse gas accounting begins. Did the amount of CO2 or N2O or CH4 in the atmosphere actually go down (or stay the same, if that was the goal)?

In almost every instance I can imagine when it comes to carbon offsets, this accounting would be almost impossible to actually do on some personal level. I’ve personally tried measuring net CO2 flux from a plant before. It sucks. A lot. Plants breathe both in and out, the machines involved can be temperamental, and the time of day and year both matter. Multiply that problem by the scale of an entire forest and we’re rising to the level of the challenge here.

At its best, carbon offsetting is often a long-term play. A tree isn’t sucking an amount of CO2 out of the atmosphere permanently all at once right after you plant it–it does that over the course of its life. A solar panel never really cancels out the coal power plant until the plant closes, pushed out of business by a thriving solar industry. So, we can’t even answer this accounting question at just a single point in time and be done with it!

This is why offset companies rarely offer something quite so concrete as a single acre of trees or a single ton of CO2 extracted. Instead, they offer you a “stake” in a large forest, for example. While it can be very difficult to measure (or guarantee) the carbon impact of a specific entity (like a specific tree), especially given the vagaries of the universe, it can be easier and less error-prone to estimate the average carbon impact a larger entity (like a whole forest).

So, you’ll often have two options if you want to be absolutely sure your carbon offset is actually offsetting the amount of carbon you were promised: Either take the seller’s word for it or get on the phone with them every year or so and get a check-up on just how your tree or solar panel or whatever is doing. These conversations would need to include actually measurements of greenhouse gas flux to/from the atmosphere. Best put it on your Google Calendar if you take Door #2.

Feeling a little demoralized? Sorry about that, if so. That said, these first three items were the easy ones. We’re not even to the really sticky stuff yet…

Checkbox #4: Did your offset seller not sell your offset to anyone else?

All the smart folks out there know this one as the idea of exclusivity, or more simply as the avoidance of “double-counting.” That is, do you own exclusive rights to the offset you’ve purchased?

Growing up, I remember a company advertising on TV that I could buy the naming rights to my very own star! I remember, at the time, thinking “How do they know no one living on some other planet–or on this planet!–hasn’t already named that star?”

It’s the same idea with carbon offsets. Remember our fairly generic-looking tree that we bought earlier? You know, the one that looks like just about every other tree that exists? Well, guess what: Your neighbor bought that same tree. And so did her neighbor. And her mom. Suddenly, ten people have bought the same tree, and the tree guy is pumped. He only needed one person’s cash to buy the tree, so now he gets to pocket the money from the other 9 people! And since no one can tell one tree apart from another and no one is comparing pictures of their trees, no one is the wiser.

You’ve been robbed, carbon offset-style! That one tree is still only offsetting so many emissions (assuming we make certain assumptions), so each person who bought that same tree is really buying a smaller and smaller share of its benefits. If it’s hard to prove that you’ve bought anything at all when you buy an offset, and it’s hard to know what amount of good the thing you’ve bought is doing, then it probably makes sense that it’s also hard to know you haven’t bought something someone else hasn’t already bought!

I know what you’re thinking. No one would knowingly sell the same trees to multiple people as part of an offsetting program. Think again. And it doesn’t always happen knowingly. Sometimes, I may ask for a little more money for my offsetting program than I end up needing–mistakes happen, after all. In these instances, someone’s money was redundant at some level.

So, when you are planning to get your proof of purchase (and your proof that your purchase is doing what it was advertised to do), you may also want to ask for proof that only you own the thing–or, at least–that your money was essential to the thing’s existence.

Don’t worry–our list is about to get better. Although that might depend on what you mean by “better”…

Checkbox #5: Did your offset actually lead to something that wasn’t already going to happen?

Again, all those smart folks out there have a cool term for this one: additionality. Suppose I am a pretty clever dude. I have a solar panel that I already have in my cart at Home Depot. I’m probably going to buy it anyway but, you know, I want to see if they have anything in the clearance section first. Just as I’m about to push my cart to the checkout counter, though, someone rings my cell. “Hello?” “Yes, I’d like to pay you to buy a solar panel and put it on your house! Will you do that for me?” “You bet I will!” [click]

That solar panel already exists. It’s probably going to be bought and installed somewhere–either by me or someone else. It’s eventual net impact on global greenhouse gas concentrations is more or less locked in. At best, by calling me up and buying an offset from me, you’ve subsidized a purchase I was already making, and the emissions reductions yielded by that thing were a benefit I was already planning to provide to all of us. At worst, though, I’ve once again robbed you–I pocketed your money and just did something I wanted to do for myself anyhow.

Again, I know what you’re thinking. Surely, offset purveyors don’t sell offsets for projects that they know would probably eventually happen with or without the cash from the sales of offsets. Wrong again. As just one example, a 2017 report from the EU estimated that 85% of offset projects they looked at lacked additionality! That’s a staggering number. Now, of course, in some of these instances, the offset program probably accelerated these carbon reductions, but that still could make the product a very different one than the buyers thought they were getting.

Here, I think it’s helpful to introduce a crucial concept in Environmental Science: The counterfactual. A counterfactual is a statement whose truth can only be assessed hypothetically rather than actually. This is usually because we’d need an alternative reality to our own in which to assess the statement’s validity.

Imagine we wanted to claim that climate change was responsible for a specific forest fire somewhere. That claim is a counterfactual—because we live in a world where climate change is occurring, it would be impossible to know if the same forest fire wouldn’t have occurred if climate change wasn’t happening. We’d need a second Earth, exactly the same as ours except without climate change, to know what would have happened. And we don’t got it, though one is probably in Marvel’s Multiverse somewhere…

It’s the same with carbon offsets. If a scheme to avert or capture carbon emissions is constructed, and offsets are sold, how can we be sure the plan wouldn’t have gone ahead eventually even without the offset money? Unless we can get independent assessments and investment records, among other things, we probably can’t. Even then, if a spot was identified as a good one for solar panels by one group, how can we know someone else wouldn’t have come along 20 years from now and put solar panels there anyway? We can’t.

So, let’s add it to your to-do list that you will have to convince yourself (because only you can know how much convincing you’ll need, and by what facts) that your offset did unique good that wouldn’t have happened without you.

Hang in there, we still have four more checkboxes to go! And if you thought this one was tough to noodle on, the next couple are going to be real doozies…

Checkbox #6: Did your offset yield net good and not just relocate the bad to somewhere else?

For this one, we have to decide which is more gross–the concept itself or the term for it. The term is leakage, and here’s how it works. Let’s imagine that you and your neighbors pool your money and purchase the rights to pay a company to not emit 100 tons of methane into the atmosphere. Via internal memos the company agrees to release to you as part of the deal, you’re even able to verify that the company definitely would have released that methane into the atmosphere without the deal. Whew–that was a close one, you might think.

Except, unbeknownst to you, the company decides, after taking your deal, that they still really need to get rid of all this methane. So, instead of releasing it themselves (that would violate the deal!), they find a buyer in Europe who will pay them for it; methane is a fuel, after all. So, they sell the methane, and the European company burns it, releasing its carbon (albeit now as CO2!) into the atmosphere anyway.

This scenario would be an example of leakage–we tried to curtail greenhouse gas emissions in one place but, by doing so, we just “chased” those greenhouse gasses to someplace else. In other words, the emissions still happened, just differently than they would have otherwise. They “leaked” out of our plan, right through our fingers!

It can be shockingly difficult to prevent leakage, even with the best of intentions. A classic example comes from offsets focused on reforestation/deforestation. Planting new trees is great and so is preventing old trees from being cut down! However, presumably, the market forces that were preventing new trees or endangering existing ones don’t go away when an offset scheme emerges. If you plant so many trees that there’s no more farmland left, or no more places to put roads, or no more places for that new Smashburger, it becomes inevitable that trees will get cut down somewhere, even if it’s not right where your new/saved forest is.

In fact, the link above references a report that suggests up to 92% of the carbon emissions reductions from anti-deforestation plans “leak.” That is, the deforestation just occurs somewhere else up to 92% of the time, so to speak. Again, that’s a staggering number.

I should stress too that the harms of leakage are not always just about carbon emissions. By preventing deforestation in a location, you might create a local food shortage due to a lack of farmland, which can then lead to famine or even armed conflict!

Because of leakage, carbon offsets tend to intersect with environmental racism. Because it is often wealthy buyers buying offsets from wealthy purveyors, poorly envisioned carbon offset programs can prevent emissions in environments the buyers care about but succeed only in moving those emissions to where poorer and more disadvantaged people live.

So, as you purchase your offset, you will need to make sure that there will be no unintended consequences that might undermine the very accounting of the offset itself or else lead to other unacceptable harms. Speaking of which…

Checkbox #7: Did the offset you purchased just lead to some other, non-GHG-related horrible thing happening there?

We don’t have to have leakage to have a serious moral problem arise from an offset scheme, though! Carbon offset programs can create big problems “right at home,” so to speak.

As just one example, reforestation programs in the tropics often involve purchasing land outright or, at least, acquiring harvesting and management rights. This makes sense–we don’t want people chopping down the trees we just planted or protected, right? But, in the process, native peoples often get excluded from their long-time territories as a result. These groups often don’t have ownership rights to the lands they live on, and they don’t have the money or political power to fight threats to their land sovereignty. While the many may gain some benefit from the offset program, the few may end up permanently displaced.

But this is by no means the only example of this phenomenon. It’s reasonable to assume the managers of a forest sold as part of an offset program may resist efforts to thin the stand or clean up debris from dead trees. The more wood in a forest, the more carbon it holds, after all! But this can mean a forest is more prone to forest fires, not only threatening the long-term security of the offset itself but the safety of the surrounding communities as well.

And what if, in this offset forest scheme, the owners of the forest allow unpermitted hunting and use of firearms on the land? Or plant invasive species because they grow faster? Or condone illegal dumping of garbage? Or put up so many fences that the land becomes a barrier to the natural movements of fauna? Just because a forest exists, holding carbon, doesn’t means that that forest isn’t a problem in other ways–that’s my point here.

So, to feel really good about our carbon offset, we’d like to ensure that its outcomes are as unequivocally good as possible. Seems like a low bar to clear to me…

Checkbox #8: Are the benefits of your offset going to last?

This one–the term for which is the misleading “permanence“–is probably among the most nuanced on our checklist. Suppose you bought an offset that got you several trees in a forest. They did their climate-protecting thing for 16 whole years, and then they burnt down in a forest fire, releasing all their stored carbon into the atmosphere in one big “poof.” It goes to show you that nothing, not even greenhouse gas emissions reductions, last forever!

Did you get your money’s worth out of your offset, though? On the one hand, yes–you averted 16 years-worth of climate impacts from the carbon stored in those trees. Sixteen years is a long time in the life of a human! On the other hand, the problem of climate change is a long-term one, one we will be wrestling with for perhaps centuries to come. Once those carbon emissions occur, their negative impacts will be felt. Was delaying them for a bit good enough? Some might argue yes, others no.

And here’s the thing: Both parties are probably right to some degree. It’s true: Climate change is a long-term problem, but it’s also a very immediate one. In that light, any little bit does help. Even delaying the inevitable can be a big deal! If you were terminally ill and could take a medicine that gave you an extra six months of high-quality life to live, you’d consider taking it, right? The benefit becomes even more pronounced when we consider that the future may hold even better solutions we don’t yet have (or can’t even yet imagine)! So, those 16 years of carbon reduction might well have been money very well spent.

…Or not. Maybe you view that as a wash at best. You weren’t buying a temporary carbon offset; you were buying an indefinite one. In your mind, the contract you signed has not been fulfilled! Who’s to say that your feelings aren’t justified?

All these hypotheticals beg a seemingly critical question: How long does an offset need to keep greenhouse gasses out of the atmosphere for to have been “worth it?” Forever? A year? Some random amount of time in between, subject to the whims of the Gods?

Science doesn’t have an unequivocal answer to this question, but it’s likely that delaying emissions by–or storing them for–just a year or less is probably meaningless. On the other extreme, the idea that a carbon offset could last forever is ludicrous. There are those that argue a meaningful carbon offset should last centuries. Even 100 years, for something like a reforestation project, is perhaps unreasonable in my opinion though. It’s hard for me to imagine what the world will even be like 100 years from now, so it seems fanciful to promise to protect a stand of trees from all hazards that long. Most of the planet’s population would have turned over in that time! But, for a true carbon capture and storage project, 100 years might be a paltry time period to promise! Meanwhile, many nature-based offsets seem designed to “expire” after 20-60 years, which may mean one you buy now could be worthless before you die. Is that ok?

So, it seems the “right answer” is probably between 1-200 years, but within those bounds, we enter heavily gray territory. How long is long enough? You, the purchaser, may have to decide for yourself! Make sure your offset provider specifies a warrantied length of time your offset is expected to last, and that this time frame seems suitable to you. Not all sellers provide such guarantees, so you’ll have to be a discerning buyer if you don’t want to call your seller up every year to check to see if your forest has burnt down lately.

Checkbox #9: Did you avoid letting your emissions get worse after buying your offset?

We’ve all been there. We realize we’ve gotten a bit pudgy around the mid-section, and we resolve that we’re going to do something about it! “No, this time, I really mean it! I’m going to exercise more!”

And, for a few weeks, you do! After each workout, you reach into the snack cupboard and pull out a cookie you wouldn’t normally let yourself have. “I’ve earned this,” you think. Three weeks pass, and you weigh exactly the same as when you started. “Where did I go wrong?” you lament while eating a cookie to comfort yourself.

The point is: Purchasing an offset to compensate for your contribution to the greenhouse effect is only as good as your resolve to keep your habits no worse than they already are. If you purchase an offset (work out) and, as a reward, drive twice as much (eat two cookies), guess what–you’ve essentially accomplished nothing overall. You’ll be right back where you started (or worse), except you’ll be a little poorer than you were before, so you’ll actually be a little worse off.

This is a common complaint lobbed at the entire concept of carbon offsets–they are seen as a way to tacitly condone, or even subtly incentivize, the very behaviors they are ostensibly designed to prevent. If producing emissions are bad, and the ways I’m behaving are creating emissions, I should change my behaviors, right? But changing our behaviors is hard or unpleasant! What if I love to drive? While carbon offsets can be an opportunity to find emissions reductions that otherwise might not occur, they are also an opportunity for people to fabricate emissions reductions they could have achieved themselves and just keep on doing the bad things they want to do.

In other words, they could be a way to give oneself a “free pass.” “I did my part. I’m done. I don’t need to do anything further. In fact…where’s my cookie?” If we pay to stop emissions with one hand but keep emitting with the other, at best, we’re only somewhat better off, and it’s possible we’re actually no better off. This doesn’t even touch upon the moral ambiguity of some offset programs, such as paying polluters not to pollute. That feels like paying the kidnapper not to kill the hostages, doesn’t it? And you’re going to reward yourself after doing that for a “job well done?” Some might argue you were better off using that money to clean up your own habits.

So, are you buying carbon offsets for the right reasons? Are you using them to offset carbon emissions you really can’t reduce yourself? And are you not treating them as a way to clean your conscience for all the emissions you could reduce but aren’t? And are you taking the steps to ensure that your carbon emissions aren’t increasing, such that your offsets are no longer actually offsetting the amount of emissions you’re creating?

We’ve reached the end of our “checklist!” The idea of it was not so much to thoroughly discourage you from buying offsets but rather to give you a holistic view of what it takes to do an offset right and to provide an introduction to the jargon you’ll need to know to properly assess whether an offset is a good choice.

Do you feel better or worse about offsets now? Do you disagree with any points I’ve made here? Have you heard of any promising offset schemes you’d like to share with those who are still interested? Please share your thoughts in the comments!